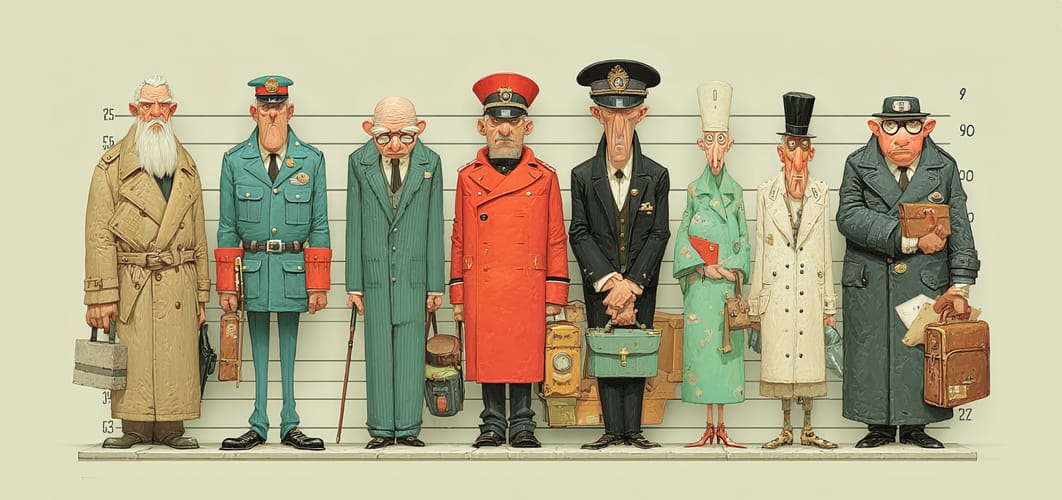

Who Are We, Where Are We Headed, and What’s the Dress Code?

Modern life has spawned a dizzying array of professions. We more or less understand why society needs them, yet the people filling these roles rarely pursue just the stated goal. They sign up for their own reasons: money, status, convenience, a short commute, parental pressure, or sheer teenage randomness when “it sounded cool” at seventeen.

That’s why most aren’t especially good at what they do. The core job feels like a burden to be endured. But even genuine enthusiasm when it's there isn’t enough to make someone truly competent. So they provide the performamce of competence, especially easy when everyone around them, including the hiring managers, is faking it too.

Even in the private sector, that is driven to market forces, where skills supposedly trump diplomas, it’s messy. Tech firms grill programmers and designers with numerous rounds of tests and interviews, yet half the hires turn out merely skilled at getting hired, not at the work itself. Add corporate politics, weak managers, and turf wars, and you get the Peter Principle in action: everyone rises to their level of incompetence.

Competence, aspiration, and delivered public benefit are three different things. They sometimes overlap, usually don’t. As a kid I noticed that some teachers are quite likable teachers yet barely knew their subject, doctors might be beloved by patients who happily prescribed homeopathy. Success metrics often diverge from real benefit — especially in long‑term, national nation-wide scope.

The loudest example is government and politics. But most other officials, and plenty of private‑sector stars in prestigeous well-paid professions, also landed there without a calling. Not to smear everyone: there are some judges, investigators, inspectors, school admins, hospital directors who belong exactly where they are. They’re just rare. These jobs are hard; few pursue them for joy, yet society still needs them, so supply appears and positions are staffed.

Sometimes you get a merely “average” worker; sometimes you get a menace like a bully prosecutor or sadistic cop. Implications can be dire, as one thing is disappointing a client; another is ruining lives.

Worse yet, when some chase the work for "enjoyment" of it, and gaining a wielding power over strangers. No one likes being a pawn in a game orchestrated by a sociopath. Luckily most aren’t villains, just ordinary people doing their jobs better than whoever might replace them.

Feeling “I am doing better than my colleagues” is a trap too: if most coworkers seem bad, odds are the system itself is broken and you might not be much better. Not everyone can be an artist or philosopher or macro‑economist. Or can we?

If AI and robots push mediocre performers out of routine roles, maybe those who stay will finally fit their seats, and society will benefit. The displaced could pursue something interesting without going broke. That sounds appealing, almost utopian, but for now, we live with current realities and manage the fallout.

Even without new tech, gradually reworking our social contract and shared understanding could help. Yet technology will come, forcing many to seek new roles — and offering a chance to find an enjoyable work where they’re actually useful and compitent.