The Eternal Trident of Struggle

In any struggle we face, any confrontation, political divide, or even everyday conflict, there are opponents, adversaries, or outright enemies. And they always come in three types, and all three exist simultaneously.

The first ones, or we could call them direct opponents — these are those who are generally on the other side from us. The second are those even more radical than we are. And the third are those on our side, but much closer to the first group than we are. Surprisingly, the main anger and the very manifestation of struggle is often directed at the third group. Though most often it's precisely the second group that's the reason we're fighting the first group at all, while the third group kind of smooths things over. The first group, correspondingly, has exactly the same situation. They have their own second and third types, and here's the funny part: when their second group is so far from the center that their enemies would initially be the opposite second group, they'll eventually unite and become almost one entity.

Briefly, this can be described as: the first are direct enemies, the second are radicals often pushing us into the conflict itself, and the third are moderate allies who seem suspiciously close to the enemies. And it's precisely on them that the main fury is most often unleashed.

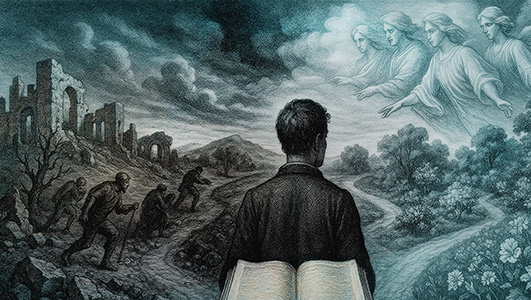

And of course, the strategy for all three is different. You need a kind of trident of approaches to be able to mount a full defense.

In military science, this is described as "external, internal, and nearest enemies," and this is a classic scheme: external enemy, internal (radicals), nearest (moderates, traitors). Freud explained this through the narcissism of small differences, where the most bitter conflicts arise precisely between those who are similar but differ in nuances. And of course, Kernighan's Law is also about this — alongside enemies, there are also worst allies. And regarding opposites, this is described by the horseshoe effect: opposite extremes (our second group and their second group) converge in methods and sometimes even become closer to each other than to the center.

There's also always what's called the gray mass, or the silent majority, or apathetic don't-care-ers. But this doesn't mean they're the center, which may not be passive at all. I don't like it when these passionate types are described as neutral. They're all on someone's side, and their outward neutrality is most often a defensive reaction. Therefore, they're either with us anyway, or essentially in league with one of the three types.

Here's an important thought: these three types always exist. But what about very narrow situations, for example, a conflict between two people? It seems that if there's only one opponent, the rule of three is violated. No, the rule remains in effect. When we descend to the level of conflict between two individuals, we begin to see that each person is a multifaceted personality, and each has their own divided parts, each with its own opinion. And within the person, there's still a struggle going on, and essentially these are our doubts that we constantly need to grapple with.

Therefore, the rule of three operates everywhere: from geopolitics and world wars to family quarrels and even our internal struggles. External, internal, and nearest enemies are always present. The question is only how we'll build the strategy of our trident.